My short e-novella “The Darkest North” is now live on Amazon!

My short e-novella “The Darkest North” is now live on Amazon!

Here’s a sample:

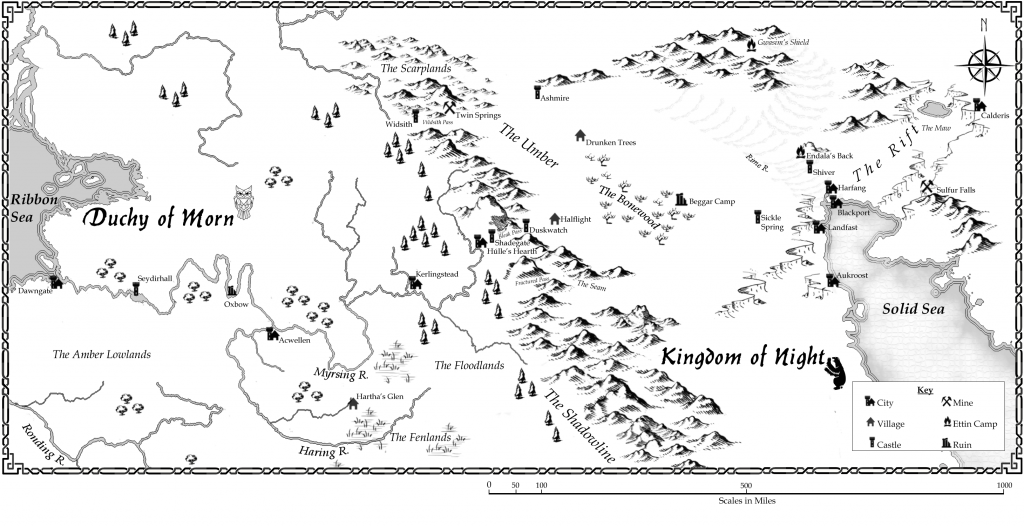

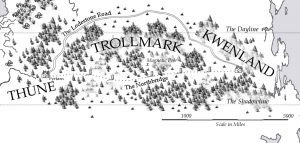

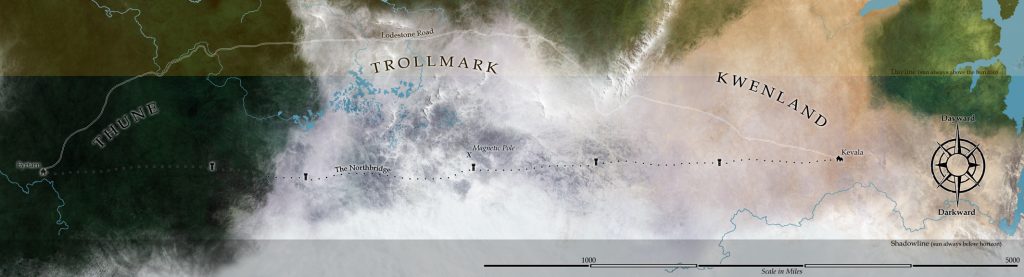

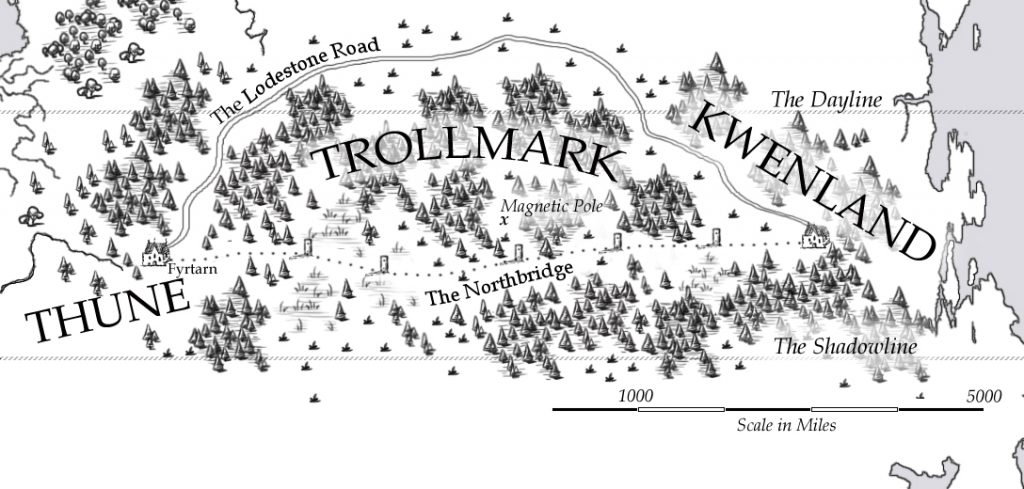

The paddleboat took me as far as it dared before the autumn rains made the river impassable. From there I found porters to carry my boxes overland, deep into the forest of ash and pines. The setting sun casts strange shadows through the trees; needle-patterns of light and dark play on the forest floor. Close to the river, it was easy enough to tell south-west, but once the trees surrounded me, everything seemed suffused with the same red glow.

My porters were natives to the area, yet even they almost missed the little clearing in the woods. I had expected a town, but the sad collection of sod huts barely warrants the title of village.

We came a few wakes too early. Once the sun set, Fyrtarn came alive. Bowls of peatmoss all along the clearing’s perimeter were set alight. The fire’s glow could be seen from miles away. And the heat was such that I soon cast off my heavier furs.

The village headsman held a sunset revel in the longhouse. All travellers were welcome, with the understanding that they would leave an offering at the village altar. As my lush furs marked me as a man of means, I took care to leave a silver mark alongside the heels of breads and iron trinkets.

I reunited with Bannik at the feast, and he introduced me to the other members of our expedition: a cook and his boy, twelve Thune porters, and eight Horned Men to serve as hunters.

That they are primitives is evident at first sight: they are tall and broad-shouldered to a man, with coarse features and the oddly protuberant gaze of a simpleton. Each man wears a voluminous headdress of dyed wool, ornamented with animal horns. The younger boys wear sheep’s horns, the elders, stag antlers. The leader of the group was unmistakable by both his size and the polished troll’s horns perched on his brow. His name is Maroth, and he is the only one of the savages to speak the One Tongue. I find myself quite hypnotized by the state of his teeth, badly worn yet quite straight and white. Bannik’s teeth, by contrast, are crooked and striped with tobacco stains.

I have no complaints with the state of the men: they all seem to be in robust health, and though the cook’s boy is a wiry thing, he is brimming with nervous energy. But I confess, I quarreled with Bannik when he insisted on bringing a seidwife on our expedition.

Seidwives: in Morn we have worked hard to be rid of their kind. I once watched one old witch being whipped through the streets for selling spells. The common women all wept, for seidwives are known to deliver children too – though I cannot see why women cannot rely on proper physicians. I will insist on such for my wife should I ever marry.

But in Thune, seidwives are still revered as priests and healers. There is a scarcity of properly trained heliophants outside the cities, and the common folk trust neither surgeons nor alchemists. Instead, they take their pains and fears to a bald witch.

To be sure, Goodwife Sohvi is much neater in her person than the old wretch I saw flogged. She is a mature woman, with a regrettably long face. But I daresay she would be still be comely, if she grew her hair out. Her dress is modest and well-kept, and she speaks the One Tongue almost without accent. With the proper cap, I almost could pass her off as the wife of a respectable farmer.

Her gaze is too bold, though. Her dark eyes invite and scorn at once. A good woman would look away more.

Bannik asked Sohvi to show me her healer’s kit. I could find no fault in her equipment: instead of charms and rune-sticks, she carries rubbing spirits and poppy-wine, along with all the usual alchemical remedies. Her knives and needles are kept sharp and clean. I continued to express misgivings, but Bannik warned me that the porters will not march without a seidwife to pray with them. And that, it seems, concluded the discussion.

“Do not pray for me,” I warned her. “I take my prayers to Súnna directly.”

She smiled enigmatically. “But can She hear you in the dark?”

Being no theologian, and no fool either, I refused to be baited.

There was no room among the little sod houses, so we bunked down in the longhouse for the winter season. So did the village livestock. For twelve long wakes, we shared the space with all manner of sounds and smells. I taught myself patience, and availed myself of every break in the poor weather to walk the torch-lit perimeter of the village.

Such noises came from the forest: the howl of the wind, the crackle of branches, the occasional cry of nocturnal beasts. But worse, oddly, was the stillness just before sunrise, when the world lay covered in fog, and all one could hear was the soft shush of the rain. In those moments, it was easy to believe there was nothing beyond our torches, but an endless expanse of icy mist.

I feared to look too long beyond the torches. Yet I feared to turn my back on the mist. One had the feeling that anything could come creeping out of it.

My novel novel, East of the Sun, is now available on Amazon as Kindle e-book and paperback.

My novel novel, East of the Sun, is now available on Amazon as Kindle e-book and paperback.